Good immigrants, Bad Politics

Authors

Armando with the support of the following grassroots organizations:

No Borders Iceland, IWW Iceland and Dýrið among others.

No Borders', Fearmongering and Xenophobia

In the wake of the racist protest "Þvert á Flokka" on the 31st of May on Austurvöllur, one of their leaders, Sigfús Aðalsteinson, a real estate speculator, appeared on the 3rd of June on a Vísir podcast, across Karl Héðinn Kristjánsson from Sósíalistaflokksins. Karl appeared confused about his affiliation with No Borders notably failing to correct the assumption that he was involved in any capacity with the organisation. He also repeated a narrow set of talking points but either omitted or failed to clarify their significance. Regrettably Sigfús was never confronted about the threats circulating in their chat before the protest, the on-site interview in which a supporter tokenized a foreign woman and hurled racist slurs, or the fact that his movement's original demands were quietly dropped.

A small group, including No Borders members, a IWW member, two Dýrið founders, a political scientist and several protesters held a discussion. In the spirit of fostering community dialogue, we decided to write this piece, presenting reflections that stem from that exchange. IWW Iceland is the Icelandic branch of the Industrial Workers of the World, a radical labor union advocating for worker solidarity and rights. Dýrið is an Icelandic grassroots organization advocating for the right to protest, which emerged from Palestine solidarity demonstrations and in response to the Icelandic Metropolitan Police’s blatant use of harassment and brute force. No Borders Iceland is part of a broader international movement that envisions a world without borders, nation-states, or the ideological and material walls that divide people. It advocates for unrestricted freedom of movement as a fundamental human right and challenges the structural violence inherent in border regimes, deportation systems, and nationalist policies. Far from being aligned with any political party, No Borders stands for solidarity, plurality, and the dismantling of racist, patriarchal, colonial, and carceral exploitative systems, whether in immigration offices, workplaces, or policy discourse. Grassroots organizations like No Borders should be respected for their autonomy, not instrumentalized. None of the authors of this text are publicly supporting any political party.

Manufactured Limbo and State paralysis

In 2023, No Borders Iceland was contacted by a group of asylum seekers and refugees after they were evicted from a camp in Hafnarfjörður. As the evictions continued throughout the summer, that group quickly grew larger, and we found ourselves dealing with a crisis largely manufactured by the Icelandic government. At our roughest estimate, at least 70 people were left homeless and unable to support themselves. Stuck in application limbo, they were ineligible for work permits and forced to rely entirely on the system for survival.

By the end of that summer, many of those we were assisting were ready to go on hunger strike to draw public attention to what they were being forced to endure at the hands of the Icelandic government. Around the same time, the government began negotiations with the Red Cross to open a shelter for these and other asylum seekers and refugees in similar situations. The result was a bare-bones facility offering little more than one hot meal per day and allowing people to stay indoors only between 17:00 and 10:00 the following morning. Outside these hours, the Red Cross and the government seemed indifferent to what happened to them or where they went.

The conditions endured by asylum seekers in the camps at Ásbrú and Hafnarfjörður are marked by persistent police harassment and general violence from authorities. Many individuals report being invited under the pretense of attending “meetings” only to be unexpectedly arrested upon arrival, creating an atmosphere of fear and mistrust. While specific cases must remain confidential to protect identities, these practices have been widely documented by multiple anonymous sources. Additionally, there are troubling accounts of illegal deportations occurring without due process, raising serious concerns about respect for legal rights. The policing of residents in these camps is often carried out by private security companies that profit from this arrangement, employing personnel who lack proper training or qualifications to work with vulnerable people, and who are primarily trained in coercion and control with little care for human rights or privacy. Beyond these violations, the general living conditions in the camps are difficult, with many people enduring prolonged uncertainty as they wait extended periods, sometimes months or even years, for responses from the Directorate of Immigration (Útlendingastofnun, UTL). This prolonged limbo exacerbates the psychological and physical toll on asylum seekers, compounding their vulnerability within a system that often appears indifferent to their plight. These are individuals who desire nothing more than to contribute positively to Icelandic society and build a stable, hopeful future.

The reality of migrant labor: Good VS. Bad foreigners?

What Þvert á flokka/Sigfús seem to be confused about, is that being an asylum seeker is not – or at least should not be – a permanent situation. Most asylum seekers are workers-in-waiting, prevented by law from starting employment, while Iceland is in dire need of migrant workers to support its economy. Tourism and fisheries are functioning thanks to migrant labor, which means many Icelandic companies and investors wouldn’t be getting rich without this workforce influx, including former asylum seekers entering the workforce. The care and service sectors are also running on migrant labor, where migrants are the designated cleaners, carers of the elderly, the young and the sick. Migrant labor is not just about profit for Icelandic investors, it is also a matter of caring for the very human needs of the Icelandic population.

However, according to the recent OECD report, migrants do worse in terms of integration in Iceland compared to other OECD countries, while ironically having a higher participation rate in the economy. This is in part due to the lack of commitment of institutions in language teaching, overall integration policy and gatekeeping tactics. Icelandic institutions only care about self-image and country-branding.

Employment for all migrants in Iceland is very regulated when it comes to who can legally work and who cannot (thus in many cases who can stay and who cannot), but in contrast very unregulated when it comes to workers’ rights and protection. Migrant workers are at high risk to experience breach of their rights at work, either through forms of wage-theft, harassment, bullying, discrimination, fire-at-will, and misinformation. Quality surveys such as Hidden People also suggest that many offenses against migrant workers go unreported or unsolved.

The lack of consequences for employers and widespread passivity of unions plays a role in these breaches of rights on the labor market. For instance, there is no legal consequence or fine if an employer does not pay wages according to the collective agreement. This means there is no reason for employers to not try to underpay a migrant worker who is uninformed or unable to speak up, because the worst that can happen would be to properly pay the worker. Iceland in that regard should take an example on Norway by also passing a law on wage-theft to protect all workers.

Servitude by Design: How Iceland Justifies Exclusion and Privatization

Through his comments about "well-behaved foreigners", Sigfús implies that some migrants are "safe", drawing a clear distinction between “good foreigners”, those who work and speak Icelandic, and “bad foreigners”, those who do not work, are accused of committing crimes, or are perceived as trying to impose new cultural norms. This dichotomy was blatantly illustrated by a supporter of Þvert á flokka on May 31st in a popular video where a foreign woman is patronized, told to say "góðan daginn", followed by racist slurs.

This division is rooted in a fundamental imbalance of power. Many so-called “good foreigners”, the “agreeable immigrants”, are kept in line and silenced about their situation in the country. For instance, residence permits tied to work or marriage can quickly become a form of coercion. Migrants, especially women, may, remain in abusive relationships, and workers endure exploitative workplaces, because without their Icelandic partner or employer, they risk losing their right to stay in Iceland. As a result, many abuses go unreported and never appear in official statistics.

Icelandic society functions in a way reminiscent of Ancient Greece, where a select few enjoyed full rights while a larger group was relegated to servitude. Today, we see a similar service class. If other forms of gatekeeping, blame is shifted to their imperfect Icelandic or a supposed lack of understanding of Icelandic culture, often constructed or exaggerated to justify exclusion.

Sigfús’ use of the health care system as an example is particularly misleading. He stokes familiar fears by suggesting that migrants are overwhelming hospitals and bringing the health care system to ruin. This trope is frequently deployed to justify privatizing essential services. In a country where even the post office has been privatized, public transport is dysfunctional, and hospitals are underfunded it’s clear that Áslaug Arna and her circle of wealth hoarders and cronies are eager to sell off the health care system to their accomplices as well. The same group of bandits benefits from unrestrained tourism, which does cause a strain on the health care system.

Moral Bankruptcy, Nepotism, Exclusion, and Iceland’s Service Class

Sigfús Aðalsteinson and Karl Héðinn Kristjánsson didn’t acknowledge the most glaring truth about unemployment figures: being officially classified as unemployed is a limited privilege, granted only to a few. Even for those foreign-born individuals who manage to enter this exclusive category, they receive only a fraction of the opportunities afforded to native Icelanders, opportunities that often come not through meritocracy, but through childhood networks, family favoritism, and informal insider systems where "Icelandic language" and knowledge of "Icelandic culture inner-workings" is used as the last barrier against overqualified immigrants. Nepotism and opportunity hoarding are the modus operandi of hiring practices and profiteering in Icelandic society.

This also raises the question: if we invest in public education, why are we not fully utilizing the immigrant workforce, many of whom had their prior education unrecognized, only to complete their studies again in Iceland? Does this not represent a significant waste of public resources and human potential?

The immigrant community is not homogeneous; individuals experience conditions and challenges in markedly different ways. This phenomenon is captured by the concept of racial triangulation, which explains how racialized groups are positioned in relation to both dominant and subordinate groups within a social hierarchy. For instance, an Icelandic manager recently praised Ukrainian workers for maintaining high service standards even under Russian artillery fire – an act that reduces their worth to sheer productivity (Sveinsdóttir 2024). This example illustrates how individuals are increasingly conditioned into a service class, where their value is assessed not on intrinsic human grounds but through Western frameworks of utility. Such narratives echo the valorization and "model minority" tropes (the "duglegur immigrant") central to racial triangulation, positioning certain racialized subjects as disciplined, resilient, and exploitable within global Western capitalist hierarchies. Thus, the lived realities of these migrants must be understood through the lens of racial triangulation, which reveals the complex and hierarchical ways in which constructions of race, ethnicity, labor, and value are structured and governed.

Crime, Public Perception, and How Data Gaps Fuel Xenophobia

Disproportionate attention is placed on the policing of minority populations across media, politics, and public discourse without any meaningful engagement with their actual demographic presence, legal status, or socioeconomic reality and contributions. This dynamic reinforces scapegoating narratives while deflecting attention from systemic inequalities and empirical realities. It is a constructed effort by populist politicians and their proxies in the mediascape and elsewhere, mirrored most recently in the manufactured panic over courier drivers.

Furthermore, the absence of detailed data on crime and lack of transparency not only hampers public accountability but also allows political actors and media commentators to exploit statistical ambiguity to advance xenophobic narratives and obscure the structural dynamics of migration and integration. As it is the case, over and over again, it all comes down to what cases are entered in the Löke (the police information system), what cases are not, what cases are prosecuted and deemed relevant for investigation, who is over-policed and who is given the benefit of doubt. Overall, fears of immigrant-driven crime are unfounded and have no basis in reality. Instead, these "global folk tales" are propagated by a population fearful of changing times, the far-right and opportunistic members of the professional managerial class (PMC), who, in collusion with the elites and their power struggles, primarily seek to advance their own self-serving interests.

The police particularly ignore right extremist threat and embolden this group since their views align with their patrons in the Independence Party. They choose to actively enable and support this bigotry; this is the classic Icelandic smoke and mirrors.

One area where Sigfús and No Borders might unexpectedly find common ground is the importance of clear, transparent, and unbiased information and statistics for making well-informed decisions. Despite heightened public perceptions of insecurity, overall crime in Iceland has actually decreased since 2001 and remained stable since 2014, according to sociologist Snorri Arnar Árnason.

Immigration, Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Sigfús, Karl and others often conflated immigration, asylum, refugee status, and various unrelated topics, so a few clarifications are necessary.

In 2024, ten countries of origin accounted for nearly 65% of immigration in Iceland: Poland (3,177), Ukraine (1,230), Romania (1,082), Lithuania (981), Latvia (597), Spain (580), Czechia (469), Germany (387), the United States (365), and the Philippines (308).

That year alone (Statistics Iceland, 2024), approximately 8,160 individuals from Eastern Europe migrated to Iceland. This includes Poles (3,177), Latvians (597), Lithuanians (981), and Ukrainians (1,230), as well as Romanians (1,082), Czechs (469), Slovaks (159), Moldovans (85), Hungarians (179), Croatians (131), and Bulgarians (70), clearly constituting the largest regional bloc.

The entirety of East, South, Central, Southeast, and Western Asia accounted for approximately 1,081 immigrants, while 913 came from Latin America. Other notable figures include Portugal (280), Italy (295) and Greece (335). However, if one excludes Venezuela (200) and Ukraine (1,230) due to their atypical geopolitical circumstances, the number of Eastern Europeans drops to 6,930, and Latin Americans to 713. Under that adjustment, the Anglosphere (United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, amounting to 683 immigrants in 2024) would constitute the third largest immigration group in Iceland, after Eastern Europe and the entirety of Asia.

Karl Kristjánsson from the Socialist Party justified stricter migration using the U.S. politician Bernie Sanders as a crutch. According to his logic, an increase in immigration leads to a surplus of labor, which employers can exploit to drive down wages, undermine collective bargaining, and erode hard-won labor protections. In this view, migrants are framed not as fellow workers seeking dignity and safety, but as competitors and instruments through which capital suppresses working-class power. He argues that capitalism "loves no borders" because porous boundaries allow capital to move freely while keeping labor fragmented. According to him, open borders benefit multinational corporations by enabling them to source cheap labor across regions, pit workers against one another globally, and bypass stronger labor protections in wealthier countries.

What Karl does not realize is that capital has always been global and this phenomena is known as TCC (Transnational Capitalist Class), a class that regardless of its opinions on immigrants is already purchasing land, resources and benefiting from low taxation. The ones benefiting from free movement across borders are the global upper class. Karl need only look around him: in 2020, Sæþór Randalsson from his party described on a popular podcast coming to Iceland after leaving the U.S. and going on a “country-shopping” trip, eventually settling here. This indicates that Sæþór himself, is the embodiment of the global upper-class that can afford moving across borders without hindrances. Villainization of immigrants is the ultimate form of alienation in our times. "Marxists" can and should know better. We live in a borderless world but only for the rich, who can move without scrutiny.

Asylum and Refugee Status

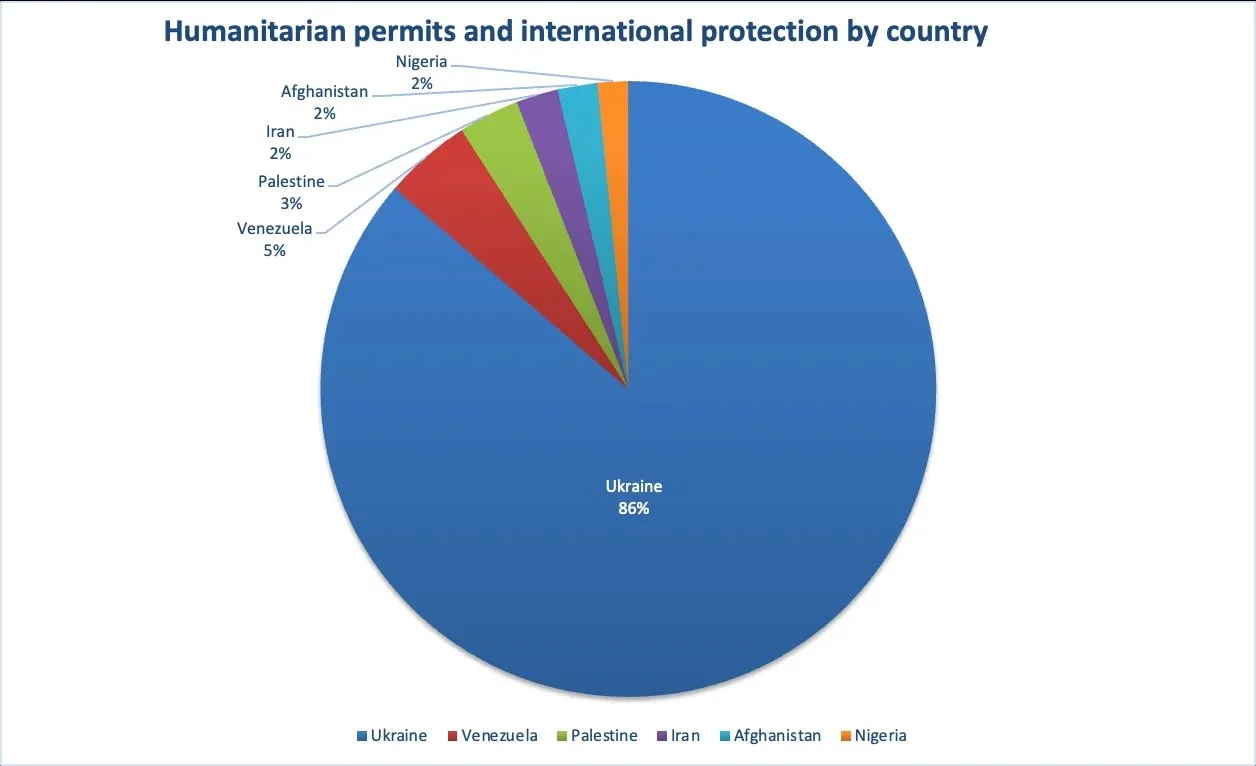

As of mid-2024, Iceland hosted approximately 8,826 recognized refugees and had 2,195 pending asylum seekers, according to the UNHCR[G1] . In the first eight months of 2024, Iceland received just over 1,400 asylum applications, a significant decline from nearly 3,000 during the same period in 2023. This decrease is attributed to a drop in applications from Venezuelan nationals, which fell from 1,500 in 2023 to only 160 in 2024, following the revocation of additional protection measures for Venezuelans. Applications from Ukrainian nationals remained substantial, with nearly 1,000 applications in the first eight months of 2024. In 2023, Iceland received 4,083 asylum applications. Of the 1,388 initial decisions made, approximately 70% (974 applications) were denied, while around 30% (414 applications) were approved. Notably, Iceland approved 154 applications from Palestinians, 47 from Syrians, 30 from Afghans, and 13 from Yemenis. Venezuelans, despite being the largest group, had only 58 approvals out of 821 decisions (7.1% approval rate). Other groups, including those from Iraq (15 rejections) or Russia (14 rejections), saw 0% approval rates.

According to the April 2025 statistics from the Directorate of Immigration in Iceland (Tölfræði verndarsviðs Útlendingastofnunar), a total of 394 asylum applications were processed between January and April 2025. Of these, 148 applications underwent substantive examination (efnismeðferð), resulting in 58 approvals and 90 rejections. An additional 189 cases were processed under provisions for mass displacement, primarily linked to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, while 32 cases were transferred under the Dublin Regulation, 18 were recognized as having protection in another country, and 7 were rejected based on the safe third country principle.

Rejection rates were highest for applicants from Venezuela (32), Iraq (12), Nigeria (8), and Colombia (6). These rejections all occurred within the framework of substantive review, meaning that the claims were assessed on their merits rather than being dismissed on procedural or jurisdictional grounds. This indicates a particularly restrictive stance towards claimants from Latin America and certain Middle Eastern and African countries.

Iceland also issued a number of humanitarian permits specifically linked to mass displacement from Ukraine. These included 26 cases of full protection, 17 humanitarian residence permits (mannúðarleyfi), and 15 grants of subsidiary protection (viðbótarvernd). These figures reflect Iceland’s continued commitment to supporting displaced persons from Ukraine, albeit through a tightly regulated framework.

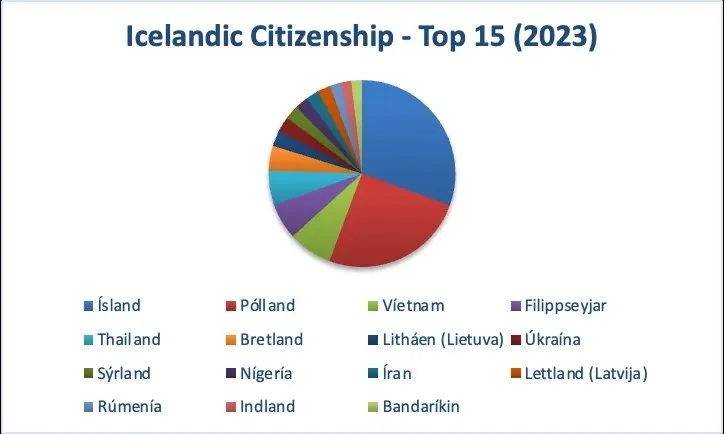

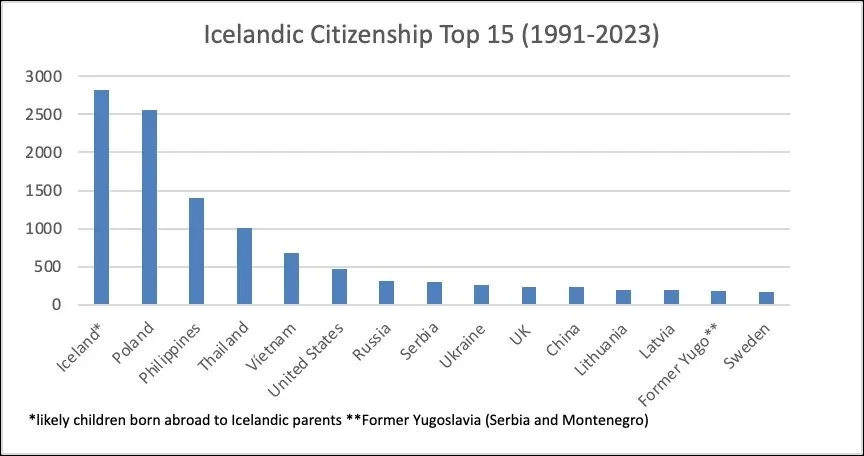

Several well-known individuals have acquired Icelandic citizenship, including musician Damon Albarn, Oscar-winner Markéta Irglová, and Katrín Lea Elenudóttir, Miss Universe Iceland 2018. Yet, when it comes to others, debates arise about their rights, highlighting how status influences acceptance. For example, Damon Albarn, a wealthy and famous man once casually visited the committee chairman asking for citizenship, which he promptly received. While there’s nothing wrong with granting him citizenship, it’s worth reconsidering the criteria for these high-profile applicants.

Source: Island.isFear Capital and Political Theater

The Minister’s attempt to frame No Borders and Ísland þvert á flokka as two extremist poles is deeply troubling. It falsely casts her government as the only rational alternative, positioning itself against "extremism" while damaging the credibility of No Borders. It is not possible to agree with the new power-seeking, opportunistic, and fueled by cronyism iteration of Socialists either. They exploit public suffering for political leverage. The aim seems to use fear ("woke-ism", "immigrants") to capitalize on disenfranchised Independence and Miðflokkurinn voters who enjoy some bigotry without the money man. The party is tweaking its new sales pitch. Hence, Karl´s confusion about whether he is a member of No Borders or not.

No Borders does not have a stake in these political games that turn fear into a form of capital.

Governments rely on public opinion, which in turn is rooted in fear, a tool exploited by rulers to maintain control, as dramatized in the film, The Village (2004), with its use of manufactured threats. Whether authoritarian or ostensibly progressive, those in power often act as “stationary bandits”, extracting resources through sustained fear and coercion. In this context, monsterization (Tyerman and Isacker 2024), the symbolic casting of racialized, non-conforming, or politically disruptive figures as existential threats, takes place.

No Borders is indifferent to these political machinations aimed at short-term selfish games and hoarding of resources. Even inside the movement, members agree to various degrees about diverse contentious topics; plurality of thought and respect, empathy and solidarity are what make a democratic society thrive. So is removing the hindrances for people to flourish, feel welcome and become constitutive members of society. Needless to say, paper pushers destroying peoples´ lives everyday, people who want to contribute to the treasury and community goes against everyone´s interest.

Demonizing immigrants is a far more convenient and politically rewarding activity for the PMC and virtue hoarders (Liu 2021) than addressing uncomfortable topics such as foreign policy, the military assault on the Freedom Flotilla within EU borders, stalling and filibuster in the parliament, fisheries policy, tax justice, the sidelining of prominent female figures within the Socialist Party, and the recently alleged scandals involving party leaders.

No Borders Collective

We call for an independent review of the Directorate of Immigration (ÚTL), transparency in citizenship decisions, and a critical reassessment of decision-making procedures.

No Borders advocates for:

· An independent review of ÚTL processing times: to ensure efficiency, accountability, and the humane treatment of applicants stuck in legal limbo

· Transparency in citizenship decisions, including scrutiny of discrepancies based on nationality and the rationale behind denials or delays

· A critical examination of the deliberation process behind immigration rulings: especially regarding the opaque deliberation processes that determine the lives of vulnerable individuals

· Urgent reform of the asylum system: people are legally barred from working, completely dependent on an unresponsive system and pushed to the brink of hunger strike to raise public awareness of these state-engineered conditions

· Improved shelter and living conditions: as it stands, residents are often forced into the streets without guidance or resources, left exposed to the elements and vulnerable to exploitation

· Oversight and accountability for conditions in asylum camps: camps in Ásbrú and Hafnarfjörður have subjected individuals to degrading conditions, limited food access, and restricted movement, reinforcing systemic neglect and dehumanization

· An end to police harassment and entrapment tactics: asylum seekers have reported being invited to supposed “meetings” only to be arrested without warning.

· A halt to illegal deportations: there is growing evidence of deportations carried out in breach of international law and Iceland’s own procedural guarantees, often targeting individuals with ongoing claims or unresolved appeals· An evaluation of how education credentials and skills are being utilized or underutilized in the Icelandic labour market, to ensure fair access and effective integration

· An independent review of tenders, police contracts, and private entities profiting from police militarization, given the well-documented involvement of foreign weapons manufacturers and select actors who promote and profit from equipping Icelandic police forces. This should also include scrutiny of the use of unqualified staff attending to refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants within UTL, government agencies or employed by private security companies surveilling asylum seekers

· Research on complaints filed against the police to determine how frequently cases are decided in favor of the complainant, and assess the effectiveness of the rulings by NEL (Nefnd um eftirlit með lögreglu, in English: Committee on Supervision of the Police)

· An investigation into politicians directly profiting from immigrant labor, fear capital, and the militarizing of Icelandic society

· Finally, No Borders welcomes the harmonization of rules envisaged under Protocol 35 which may facilitate Iceland’s alignment with EU legislation, promoting greater transparency and predictability in legal frameworks governing an array of matters that impact immigration and asylum

Works Cited

Liu, Catherine. 2021. Virtue Hoarders: The Case against the Professional Managerial Class. Minnesota University Press.

Sveinsdóttir, Rakel. 2024. “Getum Lært Mikið Af Því Að Vinna Með Erlendum Sérfræðingum.” Vísir. https://www.visir.is/g/20242523293d/getum-laert-mikid-af-thvi-ad-vinna-med-er-lendum-ser-fraedingum

The Village. 2004. Directed by M. Night Shyamalan; United States: Touchstone Pictures. Film.

Tyerman, Thom, and Travis van Isacker. 2024 “‘Here There Be Monsters’: Confronting the (Post)Coloniality of Britain’s Borders.” Review of International Studies, 1–21.