The Druze and the Crisis in Suwayda

Written by Armando Garcia. Special thanks to Mouna Nasr and Ríma Naser for their contributions.

On Mount Hermon. Druze individuals posing for a photograph at Mount Hermon, situated on the border of Syria and Lebanon, circa 1901. tereograph Cards/Prints and Photographs Division/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (digital file no. LC-DIG-ppmsca-10663). Source: Encyclopædia BritannicaMembers of the Icelandic Druze community demonstrate in front of Hallgrimskirkja in support with the people of Suweida on August 10th, 2025. Source: Daniel Thor Bjarnason

On August 10, 2025, members of Iceland’s Druze community, joined by allies, demonstrated outside Hallgrímskirkja to express solidarity with the people of Suwayda (also spelled Sweida), a predominantly Druze city in southern Syria. Protesters condemned massacres carried out by ISIS, denounced the new transitional Syrian government under Ahmad al-Sharaa (Abu Mohammad al-Julani), the former leader of al-Nusra Front, and called for immediate humanitarian corridors to deliver aid.

Suwayda today faces siege, kidnappings, and indiscriminate shelling. Civilians, often children and women, students and farmers, find themselves having to defend their villages with little or no training and limited access to weapons. As Ríma, one Icelander of Druze origin testified:

“They are sniping people in the so-called corridor, which is not even safe. Cancer and diabetes patients are dying without medicine. My cousins, just college students, are trying to protect their homes.”

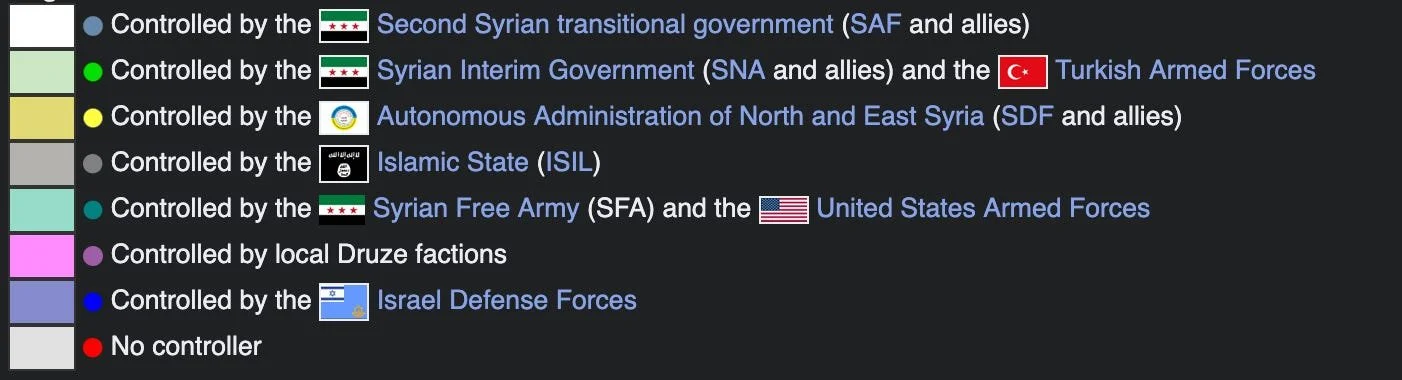

Moreover, portraying the violence as solely the work of ISIS risks obscuring the deeper reality. For the Druze community, ISIS and the Syrian government are inseparable forces. The authorities have not only deployed Daesh (also known as ISIL, Islamic State, or ISIS) fighters but also mobilized Bedouin and other Arab tribes. In this sense, and to the despair of Druze communities and their families on the ground, ISIS cannot be separated from the state, making the government the first and foremost object of condemnation.

Suwayda and The Global Druze Diaspora

Mouna, a member of the Druze community in Iceland, noted that recent comment on Vísir threatened people from Suwayda now living in Iceland, saying they should be “sent back” and falsely claiming they were Venezuelan and undeserving of international protection. Such remarks are misleading, undermine the values of dignity, safety, and fairness that Iceland stands for and expose the dangerous oversimplification and misrecognition endured by the Druze community. This kind of rhetoric reduces a complex history to crude stereotypes and falsehoods, stripping the Druze of recognition and undermining their right to safety and protection.

Given Suwayda’s layered history and its unique role as a hub for Druze identity, migration, and return, it is worth offering some clarification on who the Druze are and how their communities have taken root both in the Levant and across the diaspora.

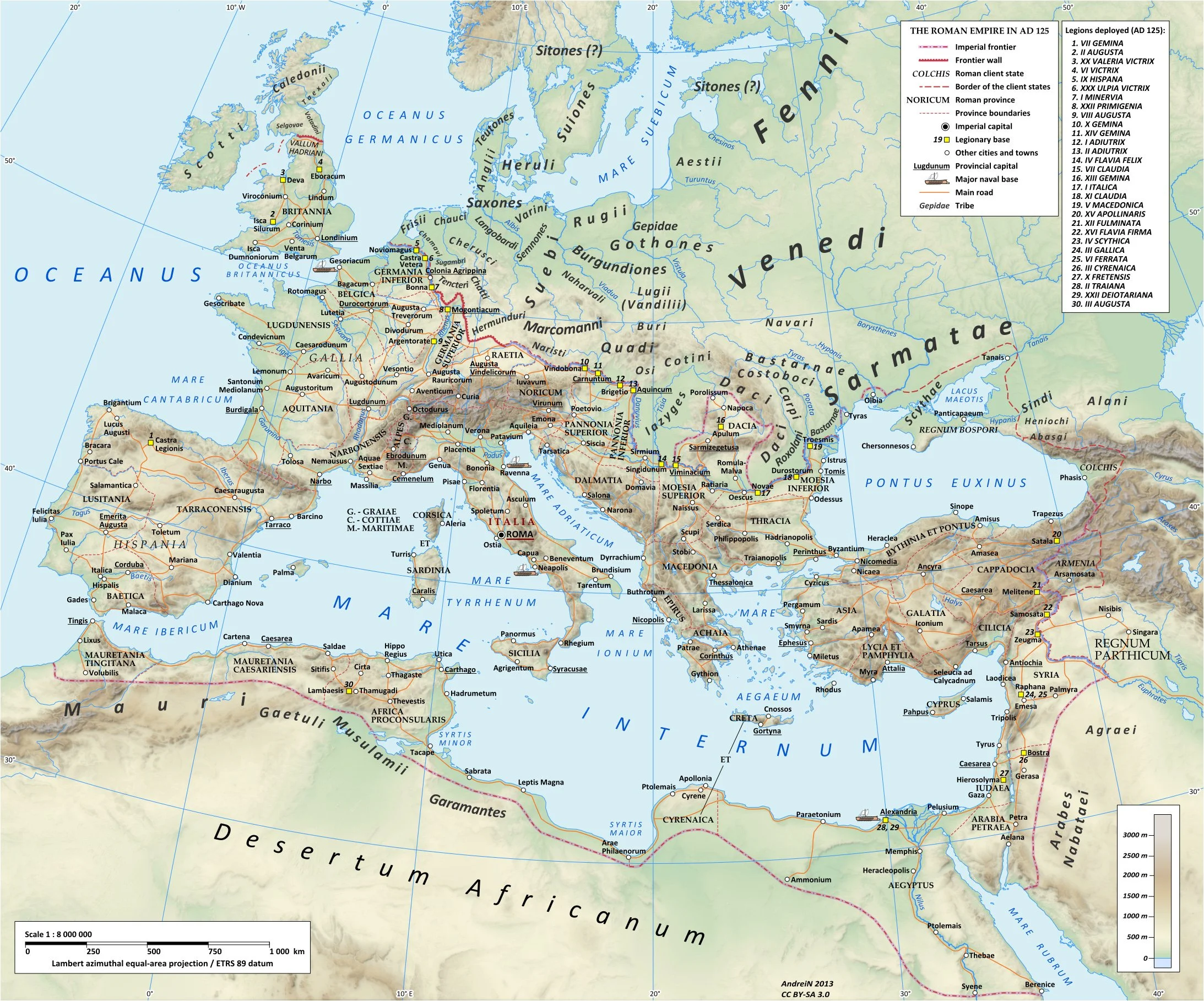

Map of the Roman Empire in 125 during the reign of emperor Hadrian, with anachronistic Germanic tribes from the time of Augustus. Source: Andrei N. (Wikipedia Commons user Andrein)Suwayda, a historically significant city in southern Syria, has a rich past dating back to the Nabataean era, when it was known as Suada and later Dionysias under Roman rule. The city was renowned for its wine production and was influenced by Hellenistic culture, with the worship of Dionysus alongside the local deity Dushara. Over the centuries, Suwayda transitioned through Byzantine, Islamic, and Ottoman rule, becoming a "titular see" after the early Muslim conquests.

Like the Kurds, the Druze are spread across several countries, separated by borders drawn after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the early 1920s. Today their population is estimated at between 800,000 and 2 million, with the majority living in Syria and Lebanon, and smaller communities in Israel and Jordan. Significant Druze diasporas also exist in Venezuela and Brazil. Their tradition, which dates back to the 11th century, weaves together various elements including Hinduism, and classical Greek philosophy. Known for their strong sense of solidarity, the Druze have played an outsized role in the history and politics of the Levant and Christianity.

Syrian-Venezuelans, primarily of Syrian origin, form the largest Arabic immigrant group in Venezuela, with migration beginning in the late 19th century as Syrian Christians and Jews fled the Ottoman Empire. The largest wave arrived during Venezuela's 1950s oil boom, reinforcing Arab cultural influence in the region. Some Syrian-Venezuelans later returned to Syria, particularly to cities like Aleppo, Tartus, and Jaramana, with Suwayda standing out as "Little Venezuela" due to its strong Venezuelan cultural presence.

There is even a street in Suwayda named named Venezuela street (Arabic:شارع فنزويلا, Venezuela Street).

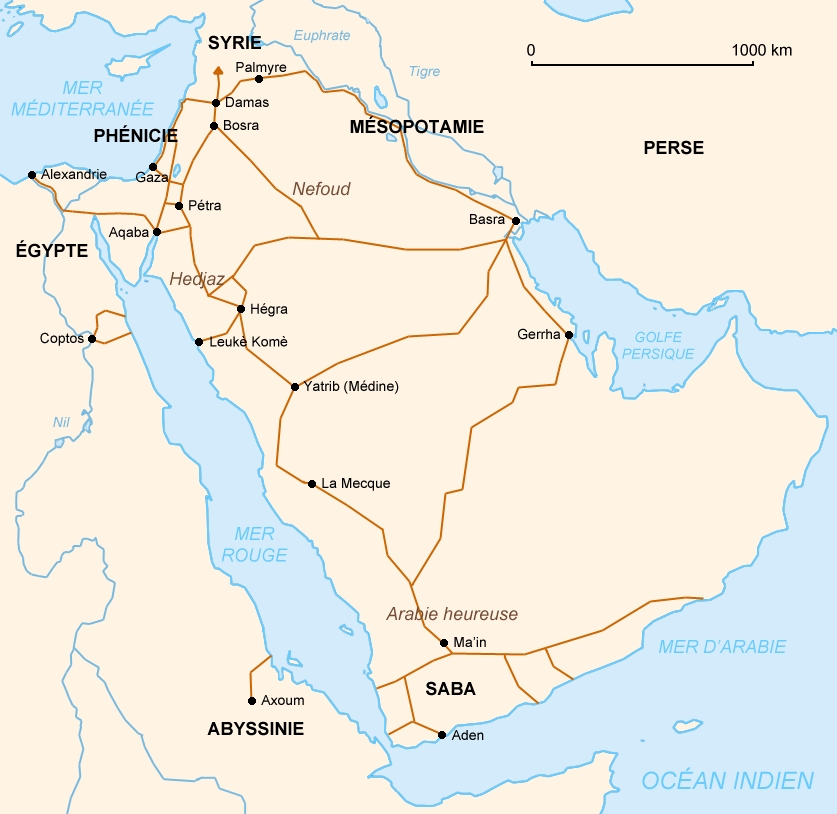

Pre-Islamic Arabia. Source: WikipediaThe majority of Syrian-Venezuelans are Druze, Roman Catholic, or Eastern Orthodox, with Venezuela hosting the largest Druze community outside the Middle East. Suwayda, home to over 73,641 inhabitants, blends Syrian and Venezuelan dialects, cuisine, and music, reflecting its deep historical ties to Venezuela.

Similarly, the Druze presence in Brazil results from the establishment of Arabic-speaking immigrants in the country since the late 19th century. Brazil received various waves of immigrants from the Middle East, mainly from the regions that nowadays comprise Lebanon, Syria and Palestine.

In early 20th-century Brazil, Druze and ‘Alawi communities formed their own institutions rather than join the Sunni-led Muslim Charitable Society of São Paulo. The Druze founded a charitable society in Oliveira (1929), later moving it to Belo Horizonte (1956), while the ‘Alawis established the ‘Alawi Muslim Charitable Society in Rio (1931), which served as the city’s main Muslim institution until Sunnis created their own association in the 1950s. Another institution, Lar Druzo Brasileiro ("Brazilian Druze Home") was established in São Paulo in 1969.

Just as the Druze in Brazil built their own institutions and integrated into broader society, the Druze in Iceland are well-integrated and contribute to the community: Mouna’s daughter recently won an award for excellence in the Icelandic language.

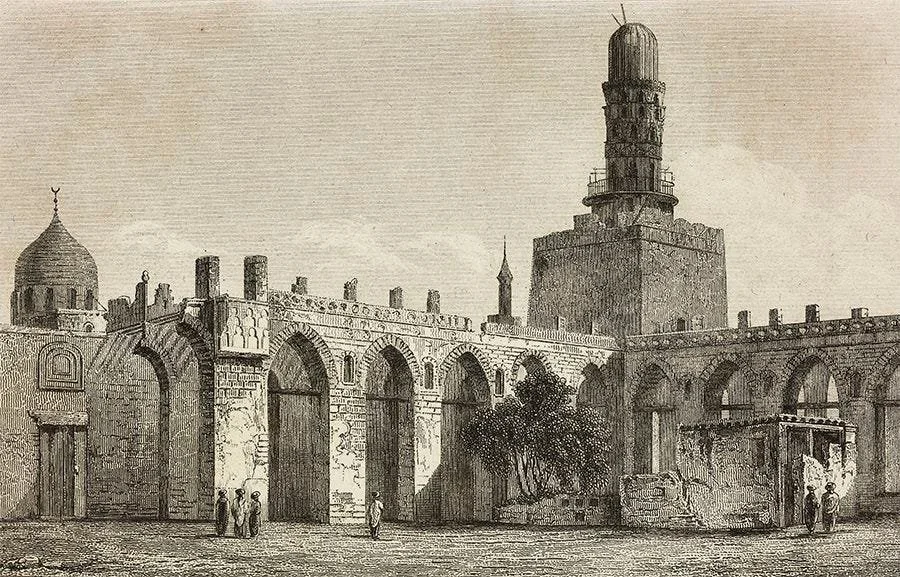

The Druze, who refer to themselves as al-Muwaḥḥidūn (meaning "the monotheists" or "the unitarians"), adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and syncretic religion that emphasizes the unity of God, reincarnation, and the eternity of the soul. Their beliefs are influenced by various traditions, including Christianity, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, and Pythagoreanism. Originated in Cairo between 1017 and 1018 CE, during the Fatimid Caliphate, the faith's foundational text is the Epistles of Wisdom.

Early 19th-century engraving of Al-Hakim Mosque in Cairo, completed in 1013, during the reign of Al-Hakim Bi-Amr Allah, the sixth Fatimid caliph. (Getty)The Druze hold the prophet Shuaib in high regard, believing him to be the same person as the biblical Jethro, and they honor figures such as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, and the Isma'ili Imam Muhammad ibn Isma'il as prophets as well.

1909 postcard depicting Ottoman Constantinople and bearing a French stamp inscribed "Levant". Source: WikipediaThe term Levant, derived from the French levant meaning "rising" and referencing the sun's ascent in the east, originally denoted the Mediterranean lands east of Italy and has evolved to specifically describe the region encompassing modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, and Cyprus. This culturally rich sub-region of West Asia, often called the "crossroads of Western Asia, the Eastern Mediterranean, and Northeast Africa", serves as a land bridge between Africa and Eurasia, with shared histories, cuisines, and traditions among its diverse populations.

Galata Tower, built in 1348 by the Republic of Genoa in the citadel of Galata (modern Karaköy) on the northern shore of the Golden Horn, across Constantinople (Fatih) on the southern shore. By A.Savin - Own work, FAL. Source: WikipediaCentral to this 11th century faith tradition is the primacy of bāṭin (inner meaning) over ẓāhir (literal interpretation), and the practice of taqiyya, meaning prudence or dissimulation.

The concept of taqiyya, originating in Shi’ism, permits believers to conceal or outwardly adopt another faith in hostile environments as a means of protecting their inner belief and ensuring communal survival. This has historically allowed for survival amid persecution. Within Druze tradition, this practice is linked to the esoteric and gnostic character of the faith, where sacred texts are accessible only to a few initiates, and secrecy is seen as essential to safeguarding religious truth.

Druze residents of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights pose together in the village of Majdal Shams as they gather for a rally against the 1981 Israeli annexation of the plateau. February 14, 2023. Source: © JALAA MAREY—AFP/Getty ImagesDruze in Israel

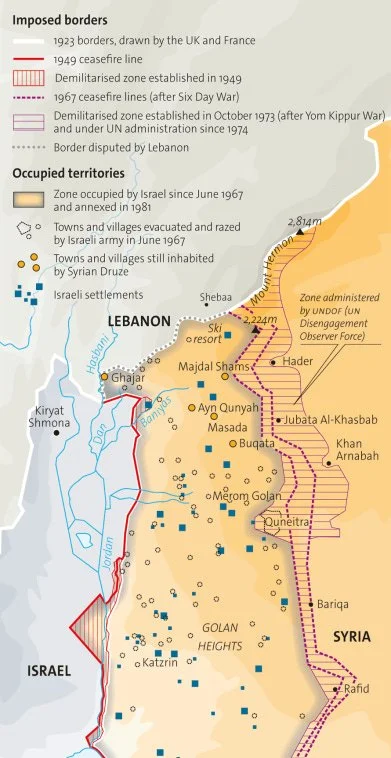

The Golan Heights, occupied by Israel since the 1967 Six-Day War, remain a contentious region, particularly for the Druze community that straddles the border between Syria and Israel. The Druze in the Golan, numbering around 20,000, face a complex identity crisis, torn between their Syrian heritage and the necessity of navigating life under Israeli control. The region's strategic importance, particularly for water resources and agricultural production, adds to the tensions.

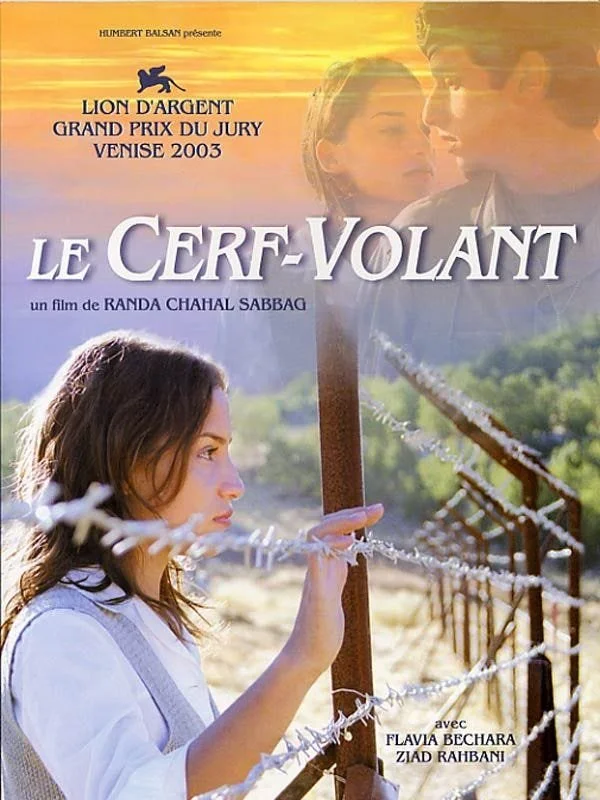

Security: an Israeli military vehicle returns from the buffer zone inside Syria, Israeli-annexed Golan Heights, 10 December 2024. Source: Jalaa Marey/AFP/GettyThe region is depicted in the 2004 Lebanese film, Le Cerf-volant, directed by Randa Chahal Sabbag and filmed near Mount Hermon. The film tells the story of Lamia, a young girl from a modest background whose life is upended when she is forced into an arranged marriage to her cousin Samy, who lives in Israeli-annexed territory. Crossing the border alone in her wedding dress, Lamia struggles to adapt to her new life, rejecting her husband and eventually falling for a Druze soldier stationed at a nearby checkpoint.

Le Cerf-volant, directed by Randa Chahal Sabbag and filmed near Mount Hermon, 2004The Druze occupy a distinct civic status in Israel. However, they are compelled into military service as a non-Arab minority, a policy rooted in ethno-citizenship discourse. They constitute only about 1.6%–2% of the Israeli army, yet are disproportionately affected by this conscription policy. Their status, initially cast as a privilege, has become contentious as younger Druze face systemic inequities such as land confiscation and underinvestment in their communities.

The Israeli state’s manipulation of Druze identity, elevating them from Arab to a separate "national" group, points to a calculated bid to preserve Jewish dominance while leveraging Druze loyalty to serve shifting political expediencies. Their distinct position now risks leaving them isolated, adrift in a society whose shifting social and political dynamics no longer guarantee the favor once extended to them.

The Syrian Conflict

The Syrian conflict has further complicated the situation, with the Golan Druze maintaining ties with their counterparts in Suwayda, sending financial support and facing the repercussions of the war, including disrupted trade and the suspension of apple exports to Syria, which had been a symbol of hope for eventual reunification.

Israel's military actions in Syria, particularly since the fall of the Assad regime, have escalated, with extensive airstrikes targeting Syria's remaining military assets. Operation Arrow of Bashan, launched by Israel, has drawn international condemnation for violating Syrian sovereignty. The operation aims to dismantle Syria's military capabilities, allegedly to prevent weapons from falling into extremist hands. However, the aggressive campaign has raised concerns about Israel's long-term intentions and the potential for further destabilization in the region.

Invaded by Israel in 1967, then annexed in 1981, the Golan Heights are considered as occupied territory by the UN. The plateau dominates Galilee and the Damascus plains, and is a key source of water, which Israel appropriates to the detriment of Syria. Source: Le Monde DiplomatiqueMeanwhile, the Druze community in the Golan continues to grapple with their dual identity, cultural roots and the realities of living in an occupied territory. The situation points to the broader geopolitical tensions and the human cost of prolonged conflict in the region.

Caught between authoritarian regimes, jihadist groups, and the high-stakes maneuvers of regional and global power politics, Druze survival often depends on expedient and provisional alliances rather than self-determination. In the Levant, sectarianism has long served as a tool of state power, entrenching the vulnerability of minority communities. When people are killed in the name of their country, they may turn instead to sectarian loyalties or seek protection from outside powers. With no safe avenues and no genuine representation, many are compelled to adopt positions they would never have chosen otherwise, less out of conviction than out of fear, and as a means of survival rather than political choice.

Suwayda's City aerial view October 2011. Shadi Alashkar. Source: WikipediaSectarianism and nationalism in the Levant reveals their interconnected evolution as strategies of state reification. Far from being a failure of nationalism or being in opposition, sectarianism is deeply intertwined in the formation of modern political subjectivity in the region, serving as tools to legitimize state authority.

By Jobas - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0. Source: WikipediaThe Syrian state, cast as a ‘state-of-empire’ and self-styled guarantor of social coexistence and political harmony, is now failing on both counts. Its reliance on violence and sectarian manipulation exposes the fragility of its rule.

Suwayda in Crisis: Sectarian Violence, External Interventions, and Humanitarian Strain

In recent years, Suwayda has been rocked by terrorist attacks, economic unrest, and violent clashes. Most recently, government-incited fighting, in which Bedouin groups were encouraged to attack the Druze community, left thousands dead this year.

The bloodshed laid bare the region’s deep-rooted tensions and Damascus’ waning grip on a province slipping further from its control.

This recent surge of violence has placed interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa under scrutiny, with the Druze community accusing his administration of committing atrocities. The crisis has drawn in outside powers as well, with the United States voicing concern and Israel launching airstrikes and claimed were aimed at safeguarding the Druze community, a group with deep historical ties to Israel.

Despite U.S.-brokered ceasefire agreements, violence in Suwayda has continued, with government forces accused of shelling villages and targeting civilians. Rima, an Icelander of Druze origin with relatives still in the region, described a dire situation:

“They are sniping people traveling through a so-called corridor, just yesterday a woman was killed. The kidnappings are still happening; a whole bus was taken, and two of the women are my relatives. The siege is ongoing.”

She added that many of those defending Suwayda are not soldiers but civilians, “my cousins are just college students, with barely any weapons experience”. According to Ríma, Suwayda does not have a formal army but relies on local villagers banding together to protect their land. She also noted the shifting reality on the ground: Bedouin tribes that once fought alongside government forces against the Druze are now clashing with those same forces, which she believes reflects a realization that “the government used them as bait”.

2025 Map of the Syrian civil war (Source: Wikipedia)The conflict has underscored the fragile state of Syria's social fabric, where minority communities like the Druze face existential threats amidst broader geopolitical tensions. The international community, including the UN, has called for an end to the violence and accountability for those responsible, but the path to lasting peace remains uncertain.

In Geneva, UN human rights experts issued a stark warning over what they described as a “targeted campaign” against the Druze in and around Suwayda Governorate. Since mid-July 2025, armed groups have carried out massacres, abductions, sexual violence, and the burning of entire villages, leaving more than 1,000 people dead and hundreds missing. Testimonies detail Druze men being humiliated with the forced shaving of moustaches, women abducted and, in some cases, executed after rape, and survivors subjected to online hate campaigns branding the Druze as “traitors” and “infidels”.

The experts condemned both the sectarian incitement driving these attacks and the complicity of interim Syrian authorities’ forces, warning that impunity has entrenched fear and silenced victims’ families. With nearly 200,000 internally displaced persons now crammed into unsafe, resource-starved shelters across Suwayda, the crisis has escalated into what UN officials describe as a humanitarian emergency demanding urgent international intervention.

Solidarity: From Reykjavík to Suwayda

The Icelandic Druze community’s demonstration is part of a broader call to action: to ensure that Suwayda’s struggle is not erased, that its people are not abandoned, and that the Druze, scattered across the Levant and the diaspora, can find dignity and security in the face of erasure. In Iceland, figures like Mouna and Ríma have become visible voices for their community, organizing vigils, speaking to the press, and lobbying for humanitarian support. Their efforts put a human face on a distant tragedy, reminding Icelanders that the crisis in Suwayda is not abstract, but one that touches families, neighbors, and colleagues here at home.

At the same time, the Druze have stressed that their struggle is not theirs alone: they have stood alongside Christians, Alawites, and others in the region, insisting on a shared future of peace, dignity, and coexistence. Solidarity across faith and ethnicity reflects both the urgency of their demands and the universal principle they embody that every community deserves safety, recognition, and the chance to live without fear.

The Icelandic Druze community, an active part of Icelandic society, with members contributing across cultural, professional, and civic life, has issued a set of urgent demands to the Icelandic government and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Þorgerður Katrín Gunnarsdóttir. These include: formal recognition of the suffering endured by the Druze people in Syria; the immediate establishment of humanitarian corridors to the besieged region of Suwayda; an independent international investigation into crimes being committed there, including the abduction of women and children; and decisive global action to halt the ongoing violence.